Summer 2025

Our quarterly briefing

As 2025 draws to a close, we briefly look at the delayed “Going for Growth” year. It has been a tough 2025, largely shaped by an unorthodox incoming United States of America (USA) administration, particularly in its trade policy.

At the beginning of the year, our message from our 2025 Autumn QEB was that “2025 is expected to be the year the economy turns a corner. [But] Geopolitical tensions and evolving trade policies could delay or alter this turnaround”. Our closing remark was that “confidence and sentiment in the New Zealand economy are what need protecting and restoring”.

While a noticeable slowdown was experienced in the middle of this year, forthcoming statistical revisions will be likely to moderate estimates of how sharply the economy stalled. Until then, at present, annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth to June 2025 was -1.1 percent.

Consumer confidence and retail sales faltered for much of the year until recently. This has started to turn, with the ANZ-Roy Morgan NZ Consumer Confidence survey in November providing positive notes and retail activity increasing by 1.9 percent in the September 2025 quarter. In addition, business confidence reached an 11-year high in November 2025. Confidence and expectations are key factors that influence economic performance and outlook.

After a tough 2025, we turn to 2026, managing expectations

As 2025 comes to an end, we look ahead to 2026. This year is widely expected to mark the economy’s stride towards stability. We agree with that sentiment, but expectations for 2026 would benefit from some managing.

As our incoming Governor, Anna Breman, takes the reins, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has reached the end of its easing cycle going into 2026, and it will stay put while monitoring the impact of its interest rate cuts working through the economy (with the usual lag of 12 to 18 months). Markets reacted quickly to the RBNZ’s signalling, for which the Governor was quick to advise that conditions went “beyond” their central projection. Stripping away the noise, and with export growth having peaked, households locking in lower mortgage rates is the principal expected tailwind for next year.

Domestic consumption will gradually take the baton in the relay and drive growth in 2026. However, our view is that the economic landing, from high inflation and interest rates combined with the uncertainty and trade shock from the USA, is concealing emerging underlying structural changes taking place in the economy.

We expect changes in economic structure to begin emerging in 2026

There is broad agreement that 2026 will be a better year than 2025. The remaining debate is around:

- What will be the pace of recovery? Will it meet expectations?

- How fast will house prices rise? Will confidence strengthen with house prices?

- What are the upside and downside risks to growth in 2026?

- What are the medium-term issues to not lose sight of?

Our perspective on these questions is shaped by the fact that the structure of our economy is changing. These changes have not yet become fully apparent as the economy has limped out of a series of shocks – from COVID-19 to high inflation (after more than a decade of low inflation), followed by the erosion of the post-WWII rules-based order and a more strategically and economically competitive world.

The outcome of these questions will be further influenced by the current and expected reforms on housing, retirement policy, and tax (with the potential for a capital gains tax), and other areas, as well as future trends such as lower population growth and technology, particularly artificial intelligence (AI).

Improved GDP growth in 2026 does not mean a return to pre-COVID-19 days. That would arguably be a rather simplistic and mechanical perspective on our economy.

We commented in our Winter QEB that “A common risk and tendency in economic forecasting is missing emerging structural change in how the economy functions, until it becomes apparent that forecasting models should have accounted for them. […] The current focus on the pace of the recovery is becoming somewhat myopic in the face of what are likely to be a larger set of underlying and emerging economic factors.”

Key themes expected for 2026

Our view is that we expect the structure of our economy to have changed, and that it will continue to change. These structural changes will begin emerging in three ways:

- First, uncertainty is reducing but will remain elevated, and business and household recovering confidence remains vulnerable

- Second, house price inflation will remain contained at a maximum of, but likely below, five percent

- Third, the level of unemployment will reduce slower than expected and may structurally stabilise at a higher level.

Additionally, we expect migration, and especially emigration, to be less predictable with many push and pull forces at play, not only in New Zealand but simultaneously in the origin and destination countries, particularly Australia and the United Kingdom (UK).

Economic volatility and uncertainty have tentatively peaked, but will not recede to historical levels

Global volatility is showing tentative signs of settling. USA tariffs, notwithstanding the upcoming Supreme Court decision, are implemented and expected to remain in force in one form or another. `

However, economic uncertainty is here to stay. The focus on the tariff uncertainty will gradually give way to broader global economic uncertainty in the coming months. Large fiscal deficits combined with sustained inflation will raise the risk of volatility in the European, Japanese, and USA bond markets. Tensions between China, the USA, and their respective allies are structural and will continue to go through cycles of flaring up followed by temporarily negotiated truces. At the same time as global conflicts (Ukraine and Gaza) appeared to be on a slow and grinding path towards resolution, the situation in Venezuela began deteriorating.

Contained house price inflation

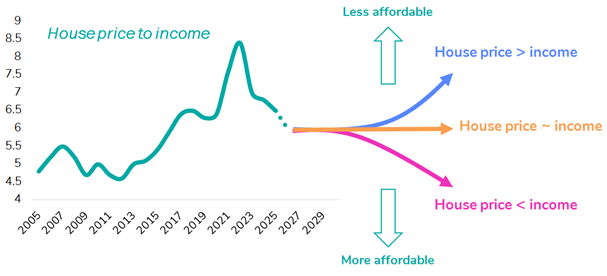

We have cautioned about relying on house price growth forecasts to drive the economic recovery. The expectation for house price inflation is currently around mid-two percent, and we expect house prices to stay broadly flat in real terms over the medium term (adjusted for income growth).

A compelling review of the demand and supply drivers for house prices shows limited sustained upside from housing because of:

- Lower immigration

- Credit standards remain tight, with mortgage rates not returning to pre-COVID levels

- Affordability remains a major constraint, albeit depending on the region

- Housing supply no longer being scarce, coupled with subdued rent growth

- The strengthening allure of other investment classes (equities and bonds, particularly in the USA).

The BERL take

Searching for consensus

As we head into 2026, and structural changes to the economy surface and gradually become apparent, the policy debate around the pace of the recovery ought to broaden. We need to ask ourselves not just how fast but also what kind of recovery it will be, and on what path it will set the economy on.

Success ought not to be solely measured by the GDP growth rate in the next 12 to 24 months but by how the New Zealand economy is positioned to sustain economic competitiveness, performance, and productivity growth over the medium term.

To respond to structural changes, a structural plan is called for

The underlying policy question remains: is the government pursuing a medium-term structural transformation of the economy (requiring short-term efforts for long-term pay-off), or is it aiming for a swifter recovery from meagre economic momentum? Ultimately, genuine structural change and a swifter recovery cannot unfold simultaneously.

However, the government are maintaining ambiguity about their ultimate economic plan and strategy. The government’s economic approach is supply-side heavy – reducing the cost of capital – and openly agnostic about the economy it wants, aside from general economic and productivity growth and focusing on ‘creating the conditions for growth’.

In the medium term, what could an economic plan and strategy look like?

Our view is that a medium-term economic plan and strategy could start with the following:

- Vertical as well as horizontal settings – The government is focused on getting ‘horizontal settings’ right for growth across the economy, for example, streamlining regulatory processes. But it could consider a balance with ‘vertical’ policies to develop priority areas of the economy or sectors, for example, targeted investments in renewable energy (without resorting to full industry-wide policies)

- Identifying value-for-money opportunities – Identify targeted areas where government intervention provides compelling value-for-money and the returns justify the cost of intervening. A good example is co-funding in research and development of the agritech sector in New Zealand, as we have a comparative advantage already

- Consistency – Establish a consensus view on the desired outlook for key aspects of the economy, including, but not limited to, the housing market. This could include establishing a clear long-term housing affordability framework agreed upon by central and local government

- Being attuned and nimble – Recognise the near-term persistent uncertainty and be prepared to adjust accordingly

- Differentiating between economic shocks and structural changes – Clarify whether changes in the global economy are economic shocks or structural changes and trends that require a medium-term response. A good example is treating commodity price spikes as a short-term shock but recognising that a global shift towards digital trade is a structural trend that will require investment in digital infrastructure and skills.

In the longer term, we need to start thinking, debating, and agreeing about New Zealand’s economic future and model

At its core, New Zealand’s economic model is a function of what drives growth and how it is shared. In this respect, the relative proportion of growth arising from, and flowing to, capital and labour is a meaningful indicator.

An intuitive “barometer” of this relationship between capital and labour is the ratio of house price to wages or income. This is because over time, this ratio is effectively the evolution of the return to capital (housing, the largest asset class in New Zealand) relative to the return to labour (income or wages). This simple ratio and relationship speak to current and future economic models.

Looking further ahead to New Zealand’s economic model, the obvious ensuing question that captures the essence of longer-term strategy and planning is – what should housing affordability look like in five, ten, and twenty-five years’ time?

New Zealand’s economic model – The housing affordability barometer

What it comes down to is the issue of bipartisan consensus

What economic future do we as a nation want? How do we make sure that our policymakers focus on a prosperous and just future for all of us, rather than on short-term gains to fit the political cycle?

Lack of political consensus is repeatedly diagnosed as the root cause of New Zealand’s failure to address enduring structural issues, from energy and climate to housing and infrastructure. Indeed, accurately or not, it is often posited as the silver-bullet solution to long-term policy challenges.

The high-level argument for political consensus is that the commitment to structural reforms, and the ensuing predictability regarding reaching better societal outcomes, would guide New Zealand towards becoming a more productive, sustainable, and inclusive nation.

Achieving political consensus requires balancing pragmatism with realistic expectations, supported by institutional structure and incentives that enable its existence and sustainability, making it a viable solution to New Zealand’s structural challenges.

The current Government has several medium-term macro and structural objectives ranging from budget surpluses and decreasing debt levels to increasing exports (doubling over the next decade), as well as the longer-term net-zero climate Paris Agreement goal by 2050. Some of these objectives are bipartisan, and some are not.

Successive governments have lacked comprehensive sets of macro and structural targets that concretely express their vision for the country’s medium-term direction. Setting such targets would allow Opposition policymakers to debate, and potentially negotiate, an agreed pathway or blueprint for the nation’s future.

BERL proposes an initial, expanded set of targets that would together provide a long-term economic direction for the economy and the country. Initial candidates, with examples of proposed targets, are a population target (to increase our scale over time), a housing affordability target, and a productivity target (to enable New Zealand to catch up to comparable OECD economies). A set of policies and reforms to achieve the respective targets would need to be developed in tandem.

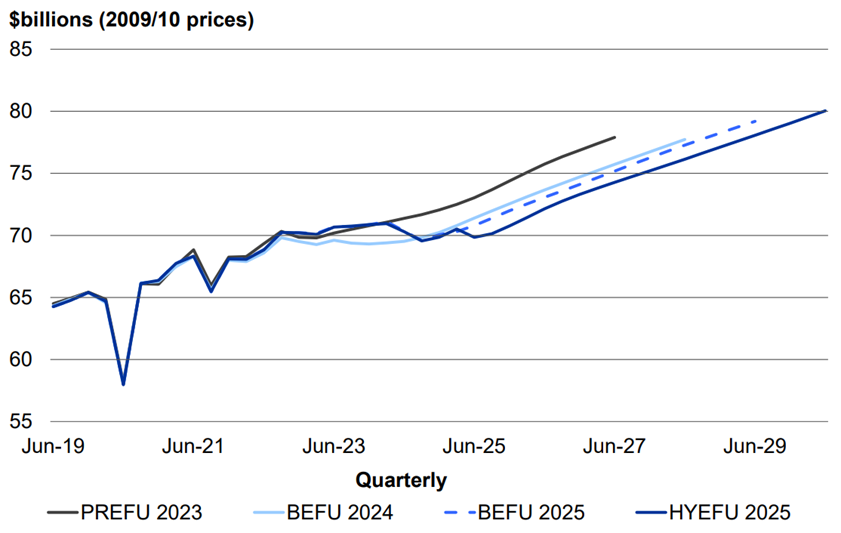

Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update 2025

The Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update (HYEFU) 2025 delivered a rather predictable outcome. Economic growth has disappointed since Budget 2025, and both Treasury’s updated forecasts and the delayed path for returning to surplus reflected that reality. Minister Willis’ response was to not overreact to small changes in projections and stay the course.

The bigger picture takeaway is by not only looking forwards, but also backwards. Looking back, Treasury forecast updates have consistently disappointed since 2023.

Real GDP forecast changes

These downside adjustments have been gradual, but they have now become sizeable. The pathway and trajectory for the economy are now less ambitious, and public expectations for the economy have effectively been managed downwards.

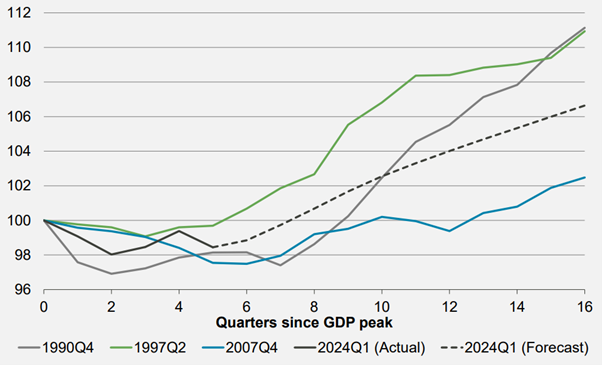

An indicator of public expectations for economic recovery is through a comparison against previous downturns. It shows a wide variation in economic trajectory coming out of a downturn. In addition, this is a blunt comparison that does not account for the differing nature of each downturn.

Comparison to previous downturns

A recovery is becoming ‘good enough’. Indeed, Minister Willis commented in her speech about her desire for an ‘upside economy surprise’ after this series of disappointing forecast revisions.

We argue instead for a more structured and deliberate plan to improve our economic trajectory.

BERL economic forecasts

Lower interest rates and mortgage rollovers are expected to drive economic recovery in coming months. As outlined above, it is sensible to temper expectations as to whether households will have the confidence to spend their higher disposable income resulting from lower interest rates. Some will understandably maintain a level of caution, or rebuild their financial buffers, in the face of still mid-four percent mortgage rates and limited wealth effect from house price inflation.

Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), has edged towards the upper edge of the RBNZ’s target band recently, reaching three percent in the September 2025 quarter. Our expectation is that ongoing spare capacity, particularly a structurally higher unemployment rate, will gradually drive inflation back to around two percent. Although lower interest rates will free up consumption, we are wary of the effects that persistent uncertainty poses.

The trade landscape is complex and fast-moving. The evolution and effects of USA tariffs are weighing on global demand; however, the New Zealand dollar (NZD) has weakened at the same time. This has lifted export returns, and higher commodity prices have supported their value, particularly in the primary sector. We expect export growth to have peaked and a slower 2026 for exporting sectors.

We expect the NZD to strengthen from 2026. As expected, the USD has been resilient leading into 2026, and will now return to its medium-term weakening trend over 2026.

Our central forecast is that the economic recovery will continue to be gradual, while we remain exposed to a wide range of plausible scenarios for the global economy over the next 6 to 12 months. We would not be surprised by changes in the global economic environment that would alter our central forecast.

BERL Forecasts

| 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | |

| Actual | Actual | Forecast | Forecast | Forecast | |

| GDP (production) | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| Consumption | |||||

| Private | -0.2 | 1 | 1.8 | 2 | 2.2 |

| Public | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Investment | |||||

| Residential | -5.6 | -9.7 | -2.5 | 5 | 6 |

| Other | -1.9 | -0.7 | 0 | 5 | 4.5 |

| Net export | |||||

| Exports | 6.8 | 14.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Imports | 0.9 | 0.3 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Prices | |||||

| CPI | 4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Exchange rate (TWI) | 71.2 | 67.9 | 69 | 70 | 69 |

| Interest rates | 5.64 | 3.67 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.3 |

| Wages (Private sector avg. earnings) | 0.4 | -4.7 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Other | |||||

| Unemployment | 4.4 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.1 |

| OBEGAL ($b, June YE) | -12.9 | -16 | -12 | -7 |

*All forecasts are to March years, except OBEGAL.

Source: BERL analysis