Autumn 2025

1.0 The Front Pages

2025 is expected to be the year the economy turns a corner. Geopolitical tensions and evolving trade policies could delay or alter this turnaround

The first quarter of 2025 was decidedly volatile as the Trump administration implemented its campaign platform, including its trade policy and tariffs. At home, the long expected economic recovery, although gradual, has started.

We do not expect the recovery to be totally thrown off course by the United States (US) economic and foreign policy, although a US economic recession cannot be dismissed outright. As the Trump administration unveils a more protectionist stance than expected the risk to the economic outlook is to the downside.

New Zealand is impacted through three channels: the direct channel, our US exports market affected by tariffs; the indirect channel, as the impact of tariffs ripples through global supply chains, including our main trading partner China; and the ‘confidence’ channel, the less tangible and measurable but consequential impact on business and household spending and investment plans.

The remaining factors affecting the outlook for 2025 are the government’s fiscal policy and Budget 2025, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s (RBNZ) monetary policy and official cash rate (OCR) for the year. Again, our base case is that both fiscal (returning to surplus and conservative budgets) and monetary (OCR reducing to about three percent) paths for 2025 will not be meaningfully altered by the incoming Trump administration (yet). But a weakening US and global economy must figure as likely economic scenarios, although this is somewhat dependent on what size tax cuts Trump gets through US Congress later in the year.

A recovering New Zealand economy weathering a fragmenting global economic order

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth for December 2024 surprised to the upside, signalling the beginning of an economic recovery cycle. But much has happened since.

While the direct impact of US tariffs will certainly be meaningful on exports affected, the broader impact on the economy will be relatively contained, including when our weakening exchange rate is taken into account. The larger concern is the ripple effects through the global economy back to us (through China in particular), and the resulting impact on domestic business and household confidence.

China is grappling with a structural economic slowdown of its own since COVID-19, and given the how interconnected the Chinese economy is with the world, further slowing will amplify the effect of the US tariffs. China is exporting its way out of its slowdown, and the Europeans are wary of a wave of cheap Chinese products flooding their markets diverted away from the US.

The worst-case scenario is an all-out global trade war. But the situation is fast-evolving and unpredictable, with policy shifts and reversals. At the very minimum, the global economic order has been unequivocally upended.

2025 is expected to see the end of the RBNZ’s cutting cycle, with a consensus view that the OCR will be reduced to about three percent. Inflation is expected to stay close to the two percent target, notwithstanding the evolving risks to the global economy. The RBNZ will take a balanced, data-dependent, and flexible approach to cutting the OCR over the coming year.

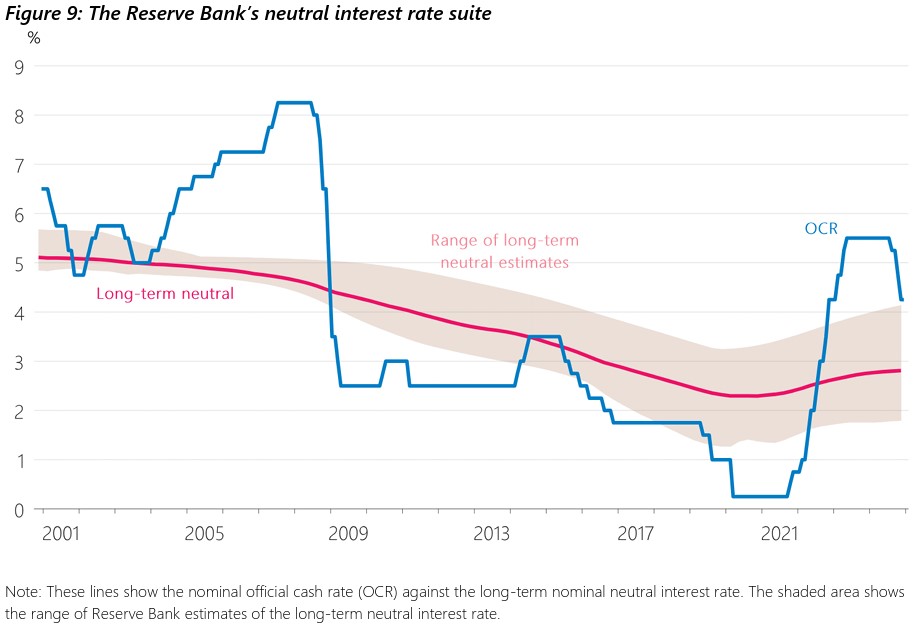

The monetary policy question for 2025 will be whether the RBNZ is keeping interest rates higher than they need to. The unsettled debate around what the neutral interest rate is, the rate at which monetary policy is neither constraining nor supporting the economy, is going to persist.

The OCR is currently sitting at the top end of the RBNZ’s estimated band for the neutral rate, and the Bank will be vigilant in retaining a tighter than needed stance on the economy. Ultimately, the neutral rate is not known with precision, particularly given the current international context.

All considered, the economic recovery will be supported by lower interest rates, but we expect the pace of the recovery to be more gradual than expected, with a downside risk that it may disappoint near-term.

Longer-term, the unavoidable question is how New Zealand, as a small open economy, positions itself in a fragmenting global economic order. The Prime Minister laid out a blueprint at a speech to the Wellington Chamber of Commerce recently, emphasising the importance of free trade and leveraging and expanding free trade agreements (The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in particular) with like-minded partners.

The US economy is on a much less certain path. The consensus is building around a slowdown in 2025, with recession risks rising

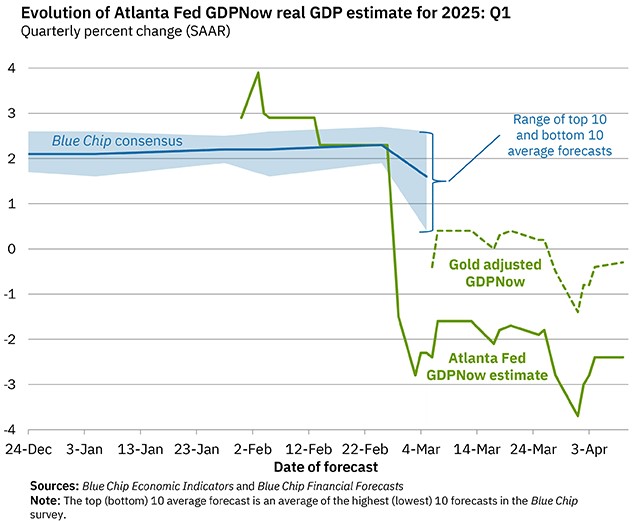

The US economy generally leads the global economic cycle. Forecasts for the US economy are being cut, as shown by the blue line below. At the same time, real time GDP indicators for the US economy have fallen off in the last few weeks although exaggerated by large recent import volumes of gold into the US, arguably to front run said tariffs. Still, the direction is unmistakable, the US economy is slowing down, with recession risks rising.

As result, waning expectations for the US economy have weakened the US dollar since January and Trump’s inauguration. A US economy slowdown will flow-on to other economies, but a weaker US dollar and lower interest rates, although both these indicators are still volatile, would provide some countervailing relief to the global economy.

Confidence and sentiment in the New Zealand economy is what needs protecting and restoring

The challenge to the economic rules-based order posed by the Trump administration is disruptive, but not fatal, to our near-term economic recovery.

It does, however, render the pace and stability of this recovery less certain, and raises longer term questions for our economic and trade policy and strategy. The less tangible and measurable, yet consequential, impact is on household sentiment and business confidence across the New Zealand economy.

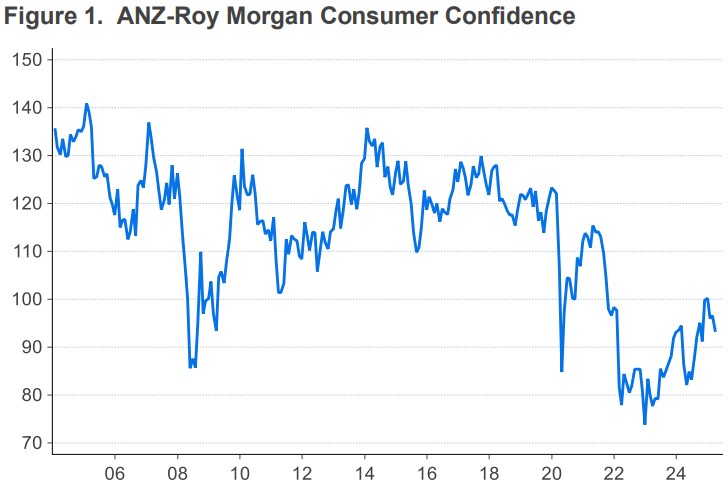

Consumer confidence is recovering, but gradually and from historic lows. Taking a long-term view (see figure below), it remains weak and vulnerable to shocks, including international ones.

Uncertainty begets uncertainty, and economic confidence is broader than direct economic and commercial links. Business investment is catalysed by certainty and predictability, while household spending varies with wealth effects.

For instance, New Zealand households have increased their exposure to US financial markets, driven by more accessible passive investment products (such as exchange-traded funds, ETFs) and buoyant asset prices in large US technology stocks. But US markets have corrected over the past weeks and days.

What can we do? Economic policy coordination and sophistication is in our control

Evidently, diplomatic efforts are part of the solution.

However, domestically, and regarding economic policy specifically, the coherence of the macroeconomic policy framework, the interaction between monetary and fiscal policy, and how it weathers uncertainty and volatility, will be important to foster New Zealand household and business confidence.

The Beehive and the RBNZ must be clear on their respective roles, and act in a coordinated fashion while remaining independent.

The RBNZ will be vigilant to the risk of remaining tight relative to the economic neutral rate, while the government will be weighing competing fiscal policy objectives. These include consolidation through achieving a surplus, attracting foreign investment (including through potential tax policy changes), and supporting confidence and the economy through this period.

Effective interaction and complementarity in the path, timing, and direction of our monetary and fiscal policies over 2025, given the heightened level of uncertainty and volatility at present, would provide a welcome anchor of predictability and certainty for households and businesses.

2.0 Special feature: Te Ōhanga Māori – The Māori economy

Earlier this year we published the fourth iteration in our series of Te Ōhanga Māori – The Māori economy reports. This iteration also included a new data dashboard for both the 2018 and 2023 iterations.

This special feature focuses on the past three iterations, specifically looking at the growth and evolution of Māori participation in the workforce over the ten years between 2013 and 2023.

The Māori population is a growing component of the domestic population

Aotearoa New Zealand’s population is growing not only in size but also in diversity. A demographic shift is underway, driven by multiple factors including migration, fertility, and socio-cultural factors. One thing is clear: Māori are a growing component of the changing domestic population.

The numbers are eye-catching. The Māori population has grown from a total of 598,600 people to 887,500 people in the ten years between 2013 and 2023. This equals a 48 percent increase. Over the same period, the total Aotearoa New Zealand population grew by 18 percent, from 4.2 million to 4.9 million. It should be noted that these numbers reflect several factors including natural population growth, an increase in the number of people identifying as Māori, and improved data collection methods in the Census.

With a fast-growing population, Māori continue to grow as a share of the Aotearoa New Zealand population, reaching 18 percent in 2023. A driving component of this population growth is a structurally younger Māori population. Thirty percent of the Māori population is under 15 years of age, compared to only 19 percent of the total Aotearoa New Zealand population. This trend is expected to continue.

The Māori workforce is growing

Looking to the future, this has important implications for Aotearoa New Zealand’s future workforce. The current and future workforce is, and will be, composed of more Māori people than in previous decades. The structurally younger Māori population is key in the sustained growth of the Māori working age population, which increased by 58 percent between 2013 and 2023, compared to 20 percent for the total population. As a result, the Māori population’s share of the Aotearoa New Zealand working-age population has increased from 12 percent in 2013 to 15 percent in 2023.

While the Māori working-age population grows, not all of this population participate in the workforce, and this can be for a number of reasons – as is true for the general population. To be classified as in the labour force, the person must be actively looking for work, or employed. This means people who are studying, or perhaps have informal care responsibilities, are not captured. Of the 625,100 working age Māori in 2023, 429,000 of them were participating in the labour force. This equates to a labour force participation rate of 69 percent.

As the Māori working-age population grows, higher numbers of Māori are entering employment at all levels, from employees to employers and self-employed. By 2023, Māori comprised 16 percent of all employees, an increase from 12 percent in 2013. At the same time, Māori grew from representing five percent of employers, up to nine percent.

Participation in work

While the actual number of Māori entering into employment, either as employees, self-employed, or employers, continues to increase at a significant rate as a share of the total Māori workforce, Māori participation in business (i.e., self-employed and employers) lags behind that of the wider population (see below figure below). This lag is particularly evident for Māori in self-employment.

Further to this, the share of the Māori workforce as either employers or self-employed has remained largely unchanged over the ten years between 2013 and 2023.

Of course, this should be viewed in the context of the structurally younger Māori population. But ultimately, lower participation has implications as businesses often play a key role in creating economic resilience and employment opportunities, including for Māori, in communities.

The Māori workforce is becoming increasingly higher-skilled

Although Māori workforce participation at the business level lags behind the wider population, the overall skill level of the Māori workforce, from employees to employers and self-employed, is increasing.

The Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) classifies occupations into five skill levels, with one being the most skilled and five being the least skilled. We categorise ANZSCO skill levels into high-skilled, skilled, and low-skilled. High-skilled includes skill levels one and two, skilled includes skill level three, and low-skilled includes skill levels four and five.

It is important to note, however, that a low skill level does not necessarily indicate that a person is “low-skilled”. Rather, it is better understood to mean that the barriers to entry into those occupations are low (for instance there are no qualification requirements).

At an overall level, for the first time across each Te Ōhanga Māori iteration, more Māori were employed in high-skilled (46 percent) occupations than low-skilled (40 percent) occupations.

This is more distinct when disaggregating by employment type. For example, 69 percent of Māori employers were high-skilled compared to only 14 percent being low-skilled, and 56 percent of Māori self-employed were high-skilled compared to 22 percent being low-skilled.

What is apparent is a structural evolution in the workforce, partly in Aotearoa New Zealand as a whole, but also through Māori becoming more skilled through education and entering higher skilled occupations.

Distribution across industries

While at an aggregate level (i.e., all Māori employed), the top five industries have remained unchanged between 2013 and 2023 (see figure below), there are emerging industries where the number of Māori employed, specifically employers and self-employed, is growing fast.

Between 2013 and 2023, the share of the Māori workforce held by the top five industries has remained concentrated at 48 percent. This is in large part supported by the ongoing growth in the construction industry, with the number of Māori employees, self-employed, or employers increasing overall by 143 percent.

It is also important to differentiate between the top industries for Māori self-employed and employers compared to Māori employees. While construction and manufacturing were the top two industries for the number of Māori employees in 2023 (37,000 each), construction and professional, scientific, and technical services were the two leading industries for Māori self-employed and employers. For Māori employees, the professional, scientific, and technical services industry was only the eighth largest industry.

Outside of construction, other industries that experienced substantial increases in the rate of Māori employed between 2013 and 2023 included:

- Professional, scientific, and technical services, up 137 percent

- Public administration and safety, up 127 percent

- Administrative and support services, up 124 percent.

For Māori businesses, while the construction industry has continued to remain the largest industry, industries such as the ones above have seen similar, often more significant increases in the number of Māori employed between 2013 and 2023.

In particular, the number of self-employed Māori in the professional, scientific, and technical services industry increased by 121 percent (up to around 3,300) while in public administration and safety, the rate of growth was 178 percent (up to around 801).

This is not too dissimilar for Māori employers, where the number operating in public administration and safety (up 204 percent) and financial and insurance services (up 179 percent), increased substantially as well.

While at the top level, the Māori workforce has remained mostly unchanged, there are emerging industries growing as a share of the workforce. It is very likely that this trend will persist. As more Māori continue to upskill and enter high-value industries at increasing rates, we may see the structure of the Māori workforce continue to evolve.

Lifting participation

It is not news that the Māori population is young and continues to grow as a share of the workforce. What we are now seeing is that more and more Māori are reaching working age and progressing further in the workforce. Despite these trends, however, overall Māori participation as employers and self-employed lags behind the national rates. Greater participation should be supported to improve outcomes associated with entering business, such as higher incomes, job creation, and innovation.

3.0 BERL economic forecasts

The domestic economy is on the path to recovery. However, there is much uncertainty around the trajectory of this path and where the economy will eventually land, with the only layer of certainty being the downside risk. The RBNZ continues to lower the OCR which now stands at 3.5 percent. The cuts, which began in August 2024, have now started to take effect. GDP increased by 0.7 percent in the December 2024 quarter, reversing some of the declines in the June and September quarters. Looking ahead, we expect the economy to continue to grow, albeit slowly. Downside risks to this outlook include a recession in the US and the wider global economy, continued weakness in consumer confidence, and weak global demand and commodity prices. Looking out to 2026 and 2027, we expect the pace of growth to tick up but remain modest given the outlook for the global economy.

Annual CPI inflation is now within the RBNZ’s target range of 1-3 percent. As it stands, we do not anticipate the US tariffs to significantly change the outlook for domestic inflation. In the April Monetary Policy Announcement, the RBNZ notes that “Most members of the Committee consider that recent global policy developments have shifted the balance of risk for New Zealand inflation lower over the medium term. Others note that, while uncertainty around the inflation outlook has increased, the risks remain balanced at this stage.” The RBNZ will wait and watch how price levels evolve in response to the tariff policies. We do not see inflation straying outside the RBNZ’s target range over the forecast horizon. The tradeable component of the CPI is currently in disinflationary territory, while the non-tradables component remains stubbornly high in the face of high energy, rates, and insurance prices. On balance, low global oil prices and weak demand are expected to keep increases in price levels for tradables low.

So far, high commodity prices and a weak NZD have supported New Zealand’s export growth. The current government has clearly outlined its intention for future economic growth to be export driven. However, the US tariff policies have dampened the outlook. As with other aspects of the economy, the path of export growth remains to be seen as geopolitical ties evolve. Over the medium-term, we are projecting export growth to remain between 2.5 percent and 3.5 percent. The negative demand shock from the US tariffs is unlikely to be large enough to send export growth into the red. Low global oil prices, a weak NZD, and new trading partners and markets will continue to buoy growth.

The slow rate of recovery of the New Zealand economy will continue to keep import growth low. The weak labour market outlook and low consumer confidence, uncertainty for businesses in making investments, combined with a weak NZD is expected to keep import growth low.

The labour market operates with a lag and our forecasts show that unemployment will tick up slightly higher than it is now before falling again. Businesses will look for certainty and their confidence in the strength of the economy will need to improve significantly from current levels for them to expand hiring. As economic growth recovers slowly, we forecast that unemployment will reach 4.8 percent by 2027.

The government has indicated clearly that fiscal policy will remain restrictive, with a surplus still the goal. Given the current economic context of slow growth and increasing unemployment, we expect the OBEGAL balance to slide further into a deficit, before narrowing over 2026 and 2027 as conditions improve. But we believe a surplus will be difficult to achieve over our forecast horizon.