Spring 2025

Our quarterly briefing

Following the widely covered -0.9 percent gross domestic product (GDP) statistic for the June quarter, and as we approach the end of 2025, let's recap the themes we laid out for the year and those that we see coming next.

Our title for our 2025 Autumn QEB stated that “2025 is expected to be the year the economy turns a corner. [But] Geopolitical tensions and evolving trade policies could delay or alter this turnaround”.

We warned that [as the] “Trump administration unveils a more protectionist stance than expected, the risk to the economic outlook is to the downside”, [and that we consider] “the pace of the recovery to be more gradual than expected, with a downside risk that it may disappoint”. Our closing remark was that “confidence and sentiment in the New Zealand economy are what need protecting and restoring”.

Slowdown and stagnation – Sliding economic growth since COVID-19

Focusing on what is in our control: Economic policy and strategy sophistication

Rather than linger on the back-and-forth debate around the precise cause of the current economic malaise, we advised instead to consider and define the respective roles of fiscal, regulatory, and monetary policy when facing an ‘uncertainty shock’.

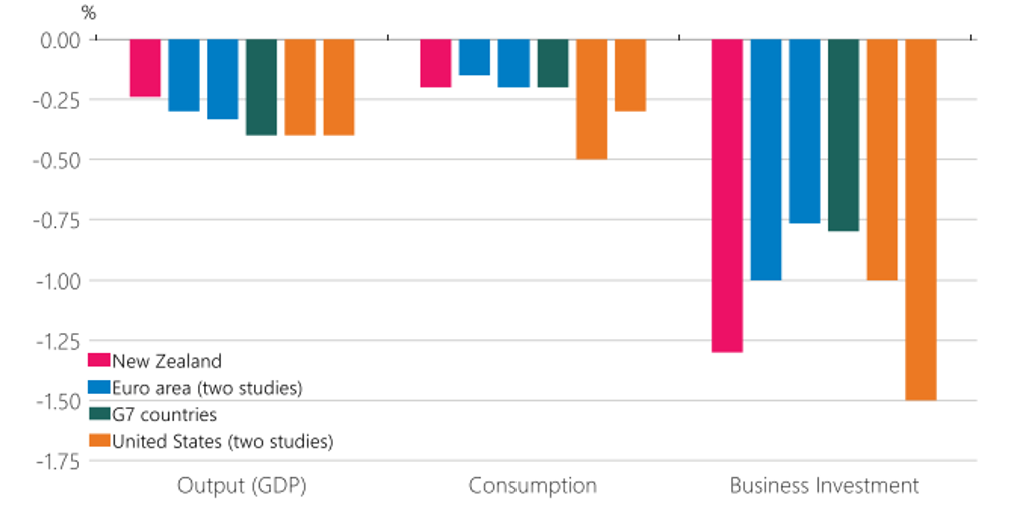

The economic impact of uncertainty (from a representative uncertainty ‘shock’)

The primary objective of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) is, after all, to maintain stable inflation around two percent, not stable economic or productivity growth per se (even if they are related). Focusing on what is in our control using our macroeconomic framework – economic policy coordination and sophistication – would serve us well in the medium-term, as we expect uncertainty to persist.

Indeed, to our surprise, the theme and debate we called for earlier this year around what is the ‘right or neutral interest rate’ partially faded (apart from more dovish economists) while the economy was weakening. We expected that “the monetary policy question for 2025 will be whether the RBNZ is keeping interest rates higher than they need to”. This question has returned following the June quarter GDP release, with calls for an official cash rate (OCR) to be ultimately lowered to around 2.5 percent.

What is effectively being debated, and understandably is difficult to ascertain, is how should interest rates compensate for economic uncertainty? Uncertainty is, after all, by definition uncertain. The real question remains whether lower interest rates can be expected to fully compensate for the combined effect of 1) global economic uncertainty and slowdown (including from tariffs); 2) weak business and consumer confidence; and 3) fiscal restraint.

However, before considering the need for fiscal stimulus, a fleshed-out and compelling economic plan and strategy is the required next step. We discuss this in the next section.

Economic volatility and uncertainty have not yet turned a corner

Looking ahead to the rest of 2025 and early 2026, leading up to the next Budget, we expect economic uncertainty to persist. Indeed, the government’s approach seems to implicitly rely on a gradual return to a ‘normalisation’ in global economic conditions that our economy would ‘tag on’ to.

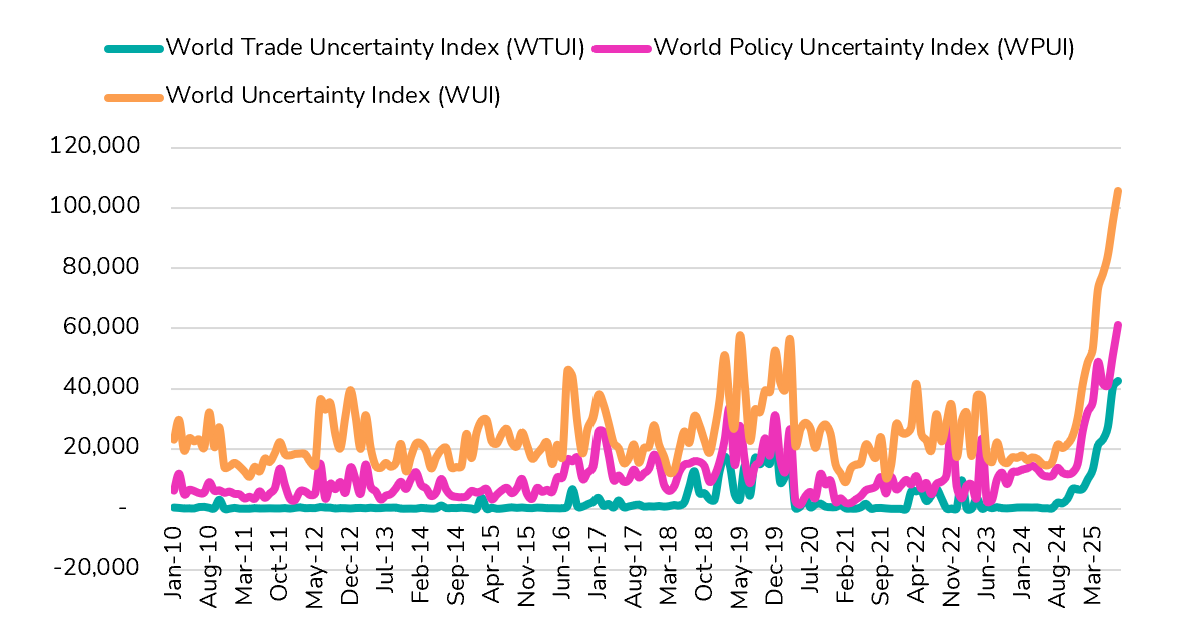

Our view is that the focus on the tariff uncertainty will gradually give way to broader global economic uncertainty in the coming months. It is not obvious to us that the world economy has yet begun gradually normalising on the ‘other side’ of tariffs. Global economic uncertainty is not only still high but has continued to worsen since Liberation Day.

Global economic uncertainty has not yet abated since taking off in late 2024 and early 2025

Our assessment is that the range of scenarios for the global economic outlook, both to the upside and downside, remains wide.

Briefly reviewing major economies:

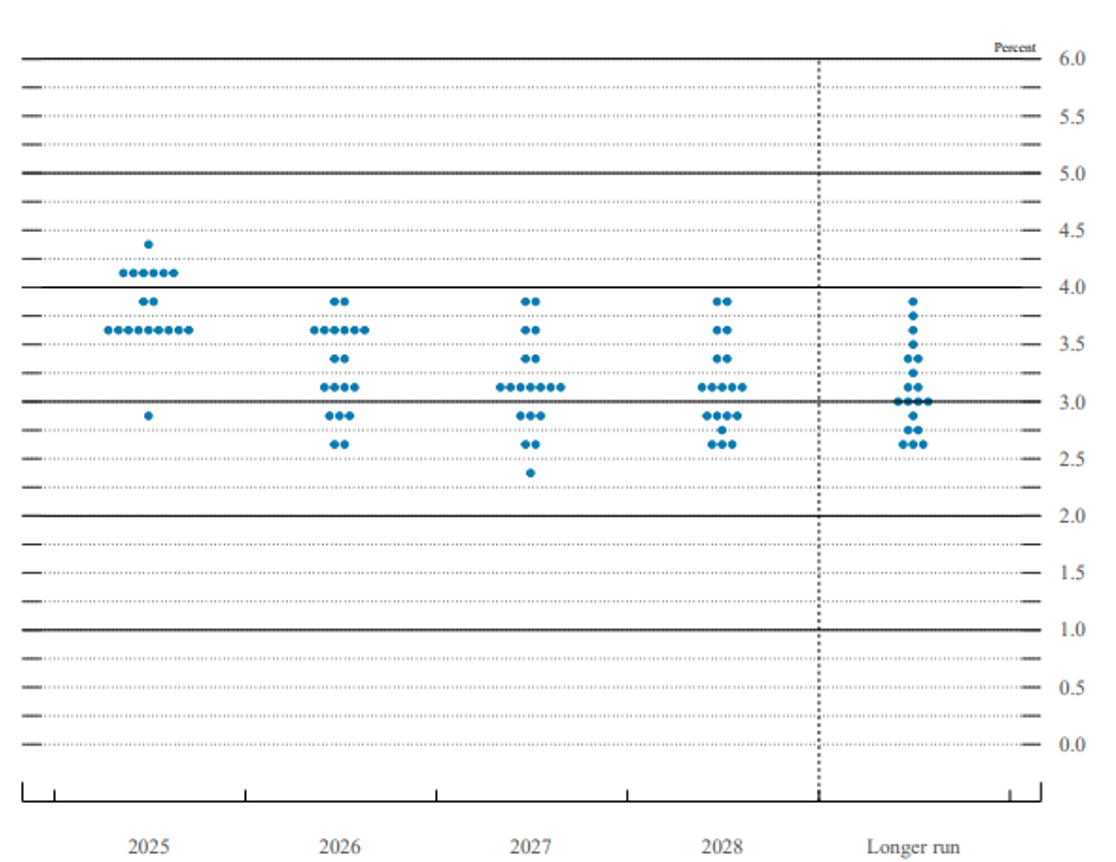

United States (US) – The labour market was weaker than expected in 2025, and the latest forecast provided by the Federal Reserve on the economy and interest rates was unusually lacking direction. The ‘dot-plots’ forward guidance on interest rates by its governing members (i.e., the Federal Open Market Committee (FMOC)) was disperse and was lacking in the provision of a clear outlook for the US economy (see chart below).

China – Experiencing conflicting signals from a recovering stock market but weakening underlying economic indicators. Strengthening equities could provide a confidence boost to consumers, or, conversely, the stock market might adjust back to the underlying economic situation.

Europe – Deemed increasingly ‘ungovernable’. Interest rates are volatile and rising off the back of high government debt risks and unpopular or unstable governments, particularly in France and the United Kingdom (UK), while Germany continues to stagnate (when not receding). The worst could be behind Europe for now or, conversely, still to come as a continuing slow-moving sovereign debt stress or crisis.

Japan – Similar political volatility and rising interest rates, raising the risk of reversing yen-carry trades on global and particularly US assets.

Other potential positive as well as negative shocks include a US government shutdown, the US Supreme Court decision on tariffs, Federal Reserve independence, and the nomination of a Trump-appointed governor in early 2026. Not to mention the evolution, and effects, of the Russia-Ukraine and Middle East conflicts (particularly on global energy markets).

US Federal Reserve Bank – FMOC interest rates forward guidance (‘dot plot’) September 2025

When facing uncertainty, think in terms of scenarios

As a high-level framework for potential scenarios over the next 6 to 12 months, we consider the following:

- Downside scenario – Economic ‘slowdown’ or ‘air pocket’ in one or more key global economies

- Central scenario – Trend economic growth but sustained inflation requiring vigilance from central banks, including potential variations of ‘stagflation’ and ‘running the economy hot’ scenarios in key economies

- Upside scenario – Also known as ‘goldilocks’, with a combination of sustained economic growth and inflation within target ranges.

While downside, central, and upside scenarios are possible, including across major economies or in a synchronised fashion, New Zealand’s economic policy settings need to be more strategic. The risk is on balance tilted to the downside, with a 50 percent probability for the central scenario, 30 percent probability for the downside scenario, and a 20 percent chance of the upside scenario.

Nevertheless, the more relevant and productive questions are: what comes next; who is responsible for what amongst fiscal, regulatory, and monetary policy; and what is the economic plan for New Zealand despite the wide range of scenarios we may face?

Ultimately, success ought not to be solely measured by the GDP growth rate in the next 12 to 24 months but by how the New Zealand economy is positioned to sustain economic competitiveness, performance, and productivity growth over the medium-term during this drawn-out recovery.

The BERL take

Economists, media commentators, and officials are processing the disappointing GDP growth release for the June 2025 quarter.

We signalled at the beginning of the year that the recovery will take longer than expected and is likely to disappoint in the near-term. At the same time, our reading of Budget 2025 was cautiously optimistic that the government is focused on medium-term economic outcomes and productivity.

Strengthening confidence through an economic plan and strategy

Our take is that the underlying policy issue lies in the lack of clarity from the government regarding whether it is conducting a medium-term structural change of the economy (requiring short-term efforts for long-term pay-off), or whether it is seeking a swifter recovery from meagre economic dynamism.

Ultimately, genuine structural change and a swifter recovery cannot unfold simultaneously.

For a swifter recovery, the impact of lower interest rates hinges, in part, on how the housing market will react. However, on this pivotal aspect, the Prime Minister and the Minister for Housing diverge in their intentions, with the latter seeking greater housing affordability and the former arguably not as much.

Taking a step back – the combination of addressing housing shortages and affordability from Minister Bishop, while Minister Willis provides the Investment Boost tax break, could be understood as a structural change plan. One that seeks to restructure investment flows, between residential and business (non-residential), to reignite productivity growth.

But cabinet ministers are maintaining ambiguity about their ultimate economic plan and strategy. The resulting lack of clarity seeds the perception that the government is not delivering on either objective (structural change and swift recovery), more so than that it is balancing the two pathways, thereby scarring confidence further. We cautioned about relying on house price growth forecasts to drive the economic recovery in our Winter QEB – a theme echoed by the RBNZ.

House prices are expected to stay broadly flat in real terms (adjusted for income growth)

Putting aside likely internal disagreements within Cabinet (both within and across coalition parties), the disappointing June 2025 GDP release ought to be a signal to the government to shift its focus from the ‘Fiscal Books’ (Year 1) and ‘Going for Growth’ (Year 2) to fleshing out a medium-term economic plan, strategy, and vision (Year 3). This was our recommendation in our Winter QEB.

What could an economic plan and strategy look like?

The government’s economic approach is supply-side heavy – reducing the cost of capital – and openly agnostic about the economy it wants, aside from general economic and productivity growth, while focusing on ‘creating the conditions for growth’.

There is scope to be more intentional, deliberate, and directing through a medium-term economic plan. The elephant in the room is whether fiscal stimulus is needed at the expense of a quicker return to fiscal surplus. However, the first question for this decision should be: stimulus to do what and to what end?

Our view is a medium-term economic plan and strategy starts with the following:

Horizontal as well as vertical settings – The government is focused on getting ‘horizontal settings’ right for growth across the economy but could consider a balance with ‘vertical’ policies to develop priority areas of the economy or sectors (without resorting to full industry policies).

Identify value-for-money opportunities – Identify targeted areas where government intervention provides compelling value-for-money and the returns justify the cost of intervening.

Consistency – Establish a consensus view on the desired outlook for key aspects of the economy, including, but not limited to, the housing market.

Attuned and nimble – Recognise the near-term persistent uncertainty and be prepared to adjust accordingly.

Differentiate between economic shocks and structural changes – Clarify whether changes in the global economy are economic shocks or structural changes and trends that require a medium-term response.

Success will be in the balance between providing consistent and clear direction while being reactive to changes and developments in the economic environment, particularly in the global economy. Economic strategy is ultimately about making linkages between near-term policy decisions and medium-term outcomes for the economy.

Differentiating between economic shocks and structural changes

At the core of this balance is differentiating between what is an economic shock that calls for a monetary policy response first and foremost and a structural change that requires gradual adjustment from industry with potential support from government. This was a focus issue in the Treasury’s 2025 Long-term Insights Briefing.

This discussion is particularly relevant to the issue of US tariffs and the stall in globalisation – is this a shock or a structural change in the world economy? Each requires its own sort of response. There is not a black-and-white answer, but it is a foundational question that shapes the role of government in the current economic times.

Our view is that economic uncertainty will persist in the near-term. The line between shocks and structural changes is blurring. We face ‘structural shocks’ that are less temporarily acute but more chronic in nature, such as the erosion of the international trade rules-based order and climate change.

On this basis, it would be practical for the government to attune its approach to the level and persistence of global economic uncertainty.

The aim should be to provide a countervailing pillar of certainty through a compelling, convincing, and clear economic plan and strategy. This would lay the foundation for assessing the case for fiscal stimulus, or not, in the lead-up to Budget 2026, depending on how the global economy unfolds.

BERL economic forecasts

The -0.9 percent contraction in the June 2025 quarter reinforced perceptions of the struggling New Zealand economy that is looking for channels to drive economic growth. Private consumption is constrained, and investment is down.

Lower interest rates and the rollover of mortgages are pinned as the looming driver of economic recovery in coming months. Whether, and to what extent, households will have the confidence to spend their higher disposable income from lower interest rates remains to be seen.

Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), has edged towards the upper edge of the RBNZ’s target band recently, reaching 2.7 percent in the June 2025 quarter. Our expectation is that inflation will remain in the upper band over the next two years. While lower interest rates will free up consumption, we are wary of the effects that persistent uncertainty poses.

The trade landscape is complex and fast-moving. The evolution and effects of US tariffs are weighing on global demand, but the New Zealand dollar (NZD) has weakened at the same time. This has lifted export returns, while higher commodity prices have supported their value, particularly in primary sectors.

We expect the NZD to remain weak over the next two years and partly offset the decrease in global demand. The USD is on a weakening path in the medium term, but we expect it to be resilient leading into 2026. Altogether, a weak NZD and low consumption will keep import growth subdued.

Our central forecast is that the economic recovery continues to be gradual, while remaining exposed to a wide range of plausible scenarios for the global economy over the next 6-12 months. We would not be surprised by changes in the global economic environment that would alter our central forecast.

BERL Forecasts

| 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 |

March years | Actual | Actual | Forecast | Forecast | Forecast |

GDP (production) | 1.4 | -1 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 2.6 |

Consumption |

|

|

|

|

|

Private | 0.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

Public | 2.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 |

Investment | |||||

Residential | -5.5 | -10.8 | -2 | 4 | 5 |

Other | -2.6 | -1.2 | 1.6 | 5 | 5 |

Net export |

|

|

|

|

|

Exports | 2.1 | 18.2 | 1.9 | 4 | 2.3 |

Imports | -15.5 | 8.3 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

Price, monetary, and wage indicators | |||||

CPI | 4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

Exchange rate (TWI) | 71.2 | 67.9 | 69.0 | 70 | 71 |

Interest rates (90-day bank bill) | 5.6 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

Wages (Private sector avg. earnings) | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3 | 3 |

Other |

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployment | 4.4 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5 | 4.8 |

OBEGAL ($b, June YE) | -12.9 | -14.7 | -14.6 | -13 | -7 |

Source: BERL analysis