Introduction

As part of BERL’s pro-bono mahi, we are taking a deeper look at how kaupapa, accountability, and value can be more explicitly communicated, and understood.

The first step on this journey is to build an understanding of kaupapa, or purpose. We’re interested in delving into:

- What are the existing and potential kaupapa of organisations?

- Are these kaupapa clearly expressed and laid out, or implied and assumed?

- What is the relationship between mission and kaupapa?

- And, how do organisations communicate their kaupapa?

We’re looking broadly at a range of organisations because we’re interested in capturing the spectrum and the nuance of the kaupapa of impact enterprises, Māori organisations, and corporate businesses.

Why do organisations exist?

In 1970 Milton Friedman from the Chicago School of Economics published an article in the New York Times saying the purpose of business is maximising profit for the shareholders. The theory had strong appeal in the face of global competition, with the idea being that the solutions to many problems could be found in free markets. In the mid-1990s John Elkington proposed the triple bottom line as a framework, bringing social and environmental aspects of organisational operations into consideration.

We now live in an age of transparency, where the internet is shining a light on how business activities are undertaken and how business decisions are made. Clients, customers, suppliers, and employees are interested in understanding why businesses exist and what their impact is in the world. And that starts with understanding their kaupapa.

What do we mean by kaupapa?

A good starting point might be to consider thinkers like Simon Sinek and Tom Bilyeu. These thinkers both emphasise the concept of a “why”, which is a baseline reason for an organisation starting up and operating.

In organisations, decision-makers make choices and take action in pursuit of the organisational strategy. The strategy serves the mission, and the mission guides the organisation toward a vision of the future. Above all of this is the reason for doing everything – an ultimate purpose, a kaupapa.

| Kaupapa/Purpose |

| Vision |

| Mission |

| Strategy |

| Actions |

One example is that of a business listed on the stock exchange. It has a vision of being a great service provider, and helping customers and communities. The business has a mission of providing the right solutions for customers, and building strong relationships in communities, and it has a strategy with internal and external actions around what products are offered, and how they develop and support their workforce to feel a part of a team and provide effective customer service. Their vision or mission may not explicitly mention profit generation, but delivering a return to shareholders is likely to be part of their “why”. Is that their ultimate kaupapa though?

Our aim is to explore kaupapa by inviting thought leaders in Aotearoa to contribute through a webinar, having a podcast kōrero, and writing website articles.

Our thought leaders on kaupapa

Podcast – Daniel Bar, bitfwd

Daniel Bar is the founding director of bitfwd (比特未来), Venture Partner at Collider Ventures (Collider.vc), and an impact entrepreneurship fellow at the Edmund Hillary Fellowship (EHF.org). As an entrepreneur and investor in the decentralised web space, Daniel’s work contributed to the establishment of Blockchain and crypto communities, and the venture ecosystem in the APAC region since 2015.

Webinar – Louise Aitken, Ākina

Louise is a strong advocate for social responsibility and impact, driven to make meaningful change by putting positive impact at the heart of our economy. She leads a talented and passionate team of impact, procurement, investment and consulting experts, providing support, capability and thought leadership both across New Zealand and internationally.

Louise joined Ākina in 2016, following a successful corporate career, which included the management of New Zealand’s largest corporate social responsibility programme. She sits on the Board of the Impact Enterprise Fund (New Zealand’s first impact investment fund) and on the National Advisory Board for Impact Investing Network Aotearoa New Zealand.

Webinar – Traci Houpapa, Federation of Māori Authorities (FOMA)

Traci is an award winning company director and a recognised industry leader. She is also a trusted advisor to Māori, Government, and public and private sector entities on strategic and economic development. Traci is known for her strong and inclusive leadership and her clear focus on building the wealth and prosperity of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Traci has been named as one of the top ten most influential women in New Zealand agribusiness and the Listener’s top ten influencers in New Zealand. She won the Westpac Fairfax Media Women of Influence Board and Management award and has been named on Westpac’s New Zealand Women Powerbrokers list. Traci has been awarded the Massey University Distinguished Alumni Service Award for services to New Zealand agribusiness and Māori, and named amongst the BBCs 100 Most Influential Women in the World. Traci is a Chartered Fellow of the New Zealand Institute of Directors, the highest level of the IODs Chartered categories, making her a nationally recognised role model for other directors and business leaders.

Traci has an MBA from Massey University and is a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit, a Justice of the Peace and a Marriage Celebrant.

Webinar – Tim Jones, The Grow Good Guy

Tim specialises at working with individuals and organisations to help them tap into their Purpose Fuelled Performance, assisting them in the transition to becoming a force for good - hence Grow Good. His purpose-focused consulting, coaching and training programmes are specially designed for those that want to use their skills to achieve meaningful goals in life and work.

Since staring his business he has worked with organisations such as Meridian Energy, The Chia Sisters, CoGo, Bivouac Outdoors, and Cookie Time to name a few. His business is one of New Zealand's founding B Corps and also B Corp Ambassador for NZ. More recently he’s been co-teaching the University of Canterbury MBA Programme "Creating Impact-led Enterprises". That's why he's New Zealand's #1 B Corp and Purpose specialist!

Guest article – Billy Matheson, The Experience Agency

Kia ora koutou, my name is Billy Matheson. I am Pākehā New Zealander and I consider myself a person of the Treaty. I am a designer by training and a facilitator and strategist by profession. My professional career spans tertiary education, youth development, local government, social enterprise, and social innovation. My passion is bringing people together in ways that support positive change and new possibilities. These days I am a self-employed consultant and have the privilege of supporting a number of purpose and values-based kaupapa across New Zealand.

Guest article – Maria Ngawati, IndigiShare

Maria Ngawati is one of a team of 7 that make up the newly formed charitable organisation – IndigiShare. IndigiShare has been created to help Māori and Indigenous enterprise and entrepreneurs to access capital and support that is perpetually circulating amongst whānau, a model that most aligns with our concept of koha. We have all been called to this space as community advocates, and have a deep understanding of how Māori cultural values can help us form a new economy, a koha economy - one that is Indigenous in design, and has reciprocity as its core value.

Webinar recording - Kaupapa-led organisations

Recorded 8 October 2020, our webinar on kaupapa covers what makes an organisation kaupapa-led and how they tell the world about it.

Panelists include:

- Traci Houpapa – Federation of Māori Authorities

- Tim Jones – The Grow Good Guy

- Louise Aitken – Ākina

Podcast with Daniel Bar

As part of BERL’s pro-bono mahi, we are taking a deeper look at how kaupapa, accountability and value can be more explicitly communicated, and understood.

We kōrero with Daniel Bar on kaupapa in tech start-ups and Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (see my article on DAOs). Daniel Bar is an entrepreneur and investor with primary focus on decentralised web technologies. He is the founder of Bitfwd and currently serves as Chairman. Daniel is also a Venture Partner at Collider Ventures, where his focus is on disruptive innovation in the FinTech space, and promoting equitable business models through open source systems, and cryptoeconomic empowerment.

What's the kaupapa? Guest article with Billy Matheson

“The key to creating or transforming community, then, is to see the power in the small but important elements of being with others. The shift we seek needs to be embodied in each invitation we make, each relationship we encounter, and each meeting we attend. For at the most operational and practical level, after all the thinking about policy, strategy, mission, and milestones, it gets down to this: How are we going to be when we gather together?”

In this article I want to share some thinking about what it means to be a Pākehā consultant working with purpose-based organisations in the cultural context of Aotearoa New Zealand. I want to start by suggesting that for any group or organisation to be asking themselves the question, “what’s the kaupapa?”, it is the beginning of a profound journey towards cultural self-awareness. One that I am starting to think of as a slow, but radical process.

The slow bit of this should be fairly obvious. In the 180 years since the signing of Te Tīriti o Waitangi I think we can safely say that Pākehā have not been quick on the uptake. We’ve chosen power and control over partnership and possibility at almost every turn. And we continue to enact this tradition every time we assert that we are all ‘one people’. It would appear the profound possibility of embodying an authentic treaty partnership is still dawning on the majority of New Zealanders.

But I believe it is dawning. As anyone who has stayed up to watch the sunrise can tell you, it takes a surprisingly long time to happen. And then, all of a sudden, it's happening. And then it happened. And now it's a new day and a new world. Then the whole change process slows down again because we’re in a new state. Slow. Then fast. Then slow again.

In my professional work as a strategic designer and facilitator, I have the privilege of seeing many organisations grappling with important questions of purpose, accountability, and value. While some organisations collapse these profound questions into simple and less threatening ideas like ‘strategic planning’ and ‘developing new management practices’, I see other organisations committing to processes of deep reflection and asking important and difficult questions about the cultural assumptions that underpin their work. It is this willingness to ask hard questions as a collective that I believe signals the start of a journey towards organisational self-awareness and collective responsibility.

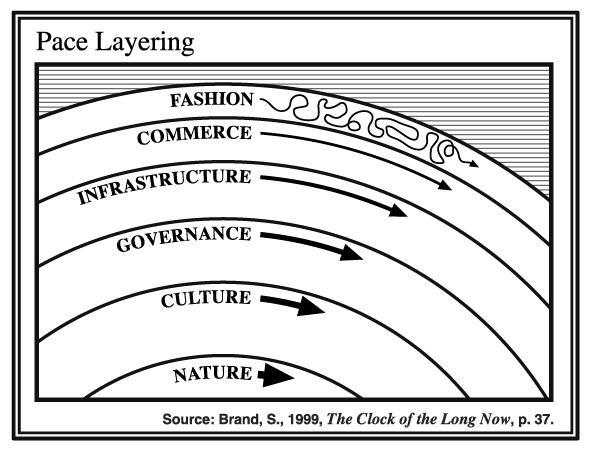

Embarking on this journey can be a daunting prospect because there is little in our modern European cultural inheritance to prepare or guide us. One of the most useful conceptual models I’ve found to help understand the challenge of doing cultural change work was created by Stewart Brand. Brand’s insight was that different ‘layers’ of our experience happen across different timescales or speeds. There is always a rift between and a lag moving from one paradigm to the next. Fashion and commerce are fast. Culture and nature are slow. And infrastructure and governance are always trying to bridge the gap between them.

My intention in pointing out that deep change is slow is not to be any kind of apologist but rather to suggest that if we are serious about understanding purpose, accountability, and value in our private organisations and public institutions, then we paradoxically need to slow down and invest more time and commit more resources to understanding how our collective identity and collective agency operate in Pākehā culture. If we want to ‘get good at change’, then I believe we first need to understand what deep, systemic, and cultural change actually involves.

This brings us to the radical part.

Here’s my hypothesis: as descendants from, and inheritors of, a European cultural worldview, ‘white’ or ‘settler’ peoples are not supposed to admit that we even have a cultural worldview. To do that would be to transgress our ancestors' cultural claims to universality (humanism), objectivity (rationalism), and autonomy (individualism). It would also require us to question our cultural sense of superiority (white supremacy).

If this hypothesis is accurate then even suggesting that we (Pākehā) might have a cultural purpose, a collective agenda, and a common need to prioritise certain kinds of outcomes over others, is to break a deeply held (and deeply unconscious) cultural taboo. The tragedy of this dynamic is that it makes it very difficult for European New Zealanders to participate in any sort of conversation about our own cultural identity, or to have any sort of coherent conversation about collective purpose, accountability, and value.

So here’s what I see as the crux of the task ahead: collective trauma can only be healed collectively. Or to put it another way, cultural problems require cultural solutions. No amount of personal growth or professional development is going to change our organisations or institutions. The root problem is not individual racism, it's not even institutional and structural racism. It is cultural self-awareness, and our disconnection from the natural world.

This is why I think it is so important that our private organisations and public institutions have the courage to ask themselves the question, “what’s the kaupapa?” Cultural self-awareness is only possible together. For the majority of us our workplace is the primary collective identity in our lives. We can only make sense of the Pākehā cultural experience – including the European diaspora and the consequences of Empire – collectively, and that means doing so in collective settings. This is not about having a few managers go on a training course.

It’s about the whole organisation deciding to transform itself as an organisation by investing in understanding and celebrating its own people and its own culture.

For me, the use of the term kaupapa, a concept from Te Ao Māori, to open up this possibility space is not about ‘political correctness’. It is a powerful and effective way to access – and therefore to make available for transformation – the dominant cultural narratives that define modern organisational life. I am not a speaker of te reo Māori but what I love about listening to the reo is the spaciousness and the plurality of meaning. It feels like a poetic and metaphorical language and at the same time one that is grounded in action and participation in the physical world.

To help understand the depth of the word kaupapa, the Māori dictionary offers these ideas:

kaupapa

- (noun) level surface, floor, stage, platform, layer.

- (noun) topic, policy, matter for discussion, plan, purpose, scheme, proposal, agenda, subject, programme, theme, issue, initiative.

- (noun) raft.

- (noun) main body of a cloak.

So when someone asks “what’s the kaupapa?”, they might simply want to know what the topic for discussion is. But they may also be asking whether the cloak we are weaving together has a strong underlying structure, or that the raft of the organisation they are joining is going to stay afloat, or that the platform we are building together is one that has integrity.

To get to the bottom of the question of purpose and accountability and value in our organisations and in our economy, we need to understand the underlying structure of the modern Western European organisation and the economy that our organisations are part of.

You don’t need to be a professor of history to understand that most of our organisational practices are military in origin. Anyone who works within a modern organisation should be able to see that the ‘British Army model’ is alive and well and quietly defining our workplace culture. Staff are the soldiers, middle management are the officers, and the executive leadership team are the generals. Concepts like strategy, chain of command, spans of control, logistics, payroll, recruitment and attrition are all military in origin and carry with them predictable consequences for the people involved.

I would argue that a very specific cultural worldview is baked into the DNA of most modern European organisations and civic institutions, one based on values of power, control, and productivity. There is nothing new about “putting profits before people”. The British Empire did it for 400 years.

If we are serious about the possibility of transforming how our organisations think about purpose, accountability, and value we need to come to terms with the militaristic and colonial origins of most modern European institutions.

I want to be very clear on this point: the problem is not structural, it’s cultural. The term ‘protestant work ethic’ is a term that some people have used to try and describe this complex cocktail of religious conflict, commercial imperatives, and moral obligation. Reviewing our mission, vision, and values is not going to make a dent in that particular hangover. As Peter Drucker famously pointed out, “culture eats strategy for breakfast”.

The question, “what’s the kaupapa?”, goes deeper than just our organisational life. We need to be taking this question into our politics and our cultural assumptions about governance and sovereignty. The underlying structure of New Zealand politics is the same Westminster model of government that administered the running of the British Empire for hundreds of years. I cannot see how we can meaningfully address any of the social, economic, or environmental challenges we face as a nation until we first decolonise and demilitarise our politics.

While I am generally supportive of representative democracy, I find it hard to understand why we are not actively investing in the reimagining and redesigning of our current outdated and adversarial political system. I cannot think of a more appropriate way to mark our bicentenary in 2040 than committing to the development of a new model of government for Aotearoa New Zealand that is based on authentic Treaty partnership.

Rather than seeing Māori and Pākehā as ‘oppositional’ or ‘dividing’ concepts, my understanding of biculturalism is that it is the key to a larger and more expansive and relational worldview. I cannot be fully me, without you being fully you. Together we help each other understand who we are and who each other is. I’ve found Jessica Benjamin’s work on ‘recognition theory’ particularly useful in articulating how this mutual interdependence works. According to Benjamin, the relational worldview is not based on “two-ness” and the either/or logic of self and other. The relational worldview is based on “three-ness” and the both/and logic of connection. In this paradigm, there is you and there is me and there is also our relationship. It is the presence of this ‘third’ that animates our experience of each other and makes it powerful.

Our relationship with one another is the kaupapa, or underlying structure, that makes meaning and possibility available to us. This is why whanaungatanga and manaakitanga matter so much whenever we gather together.

Without this space of possibility to expand into, we have little choice but to contract into defensive and conservative positions of ‘twoness’ and ‘self’ and ‘other’ and ‘us’ and ‘them’. In my experience, transformational change comes when an organisation chooses to value the quality of its relationships (internal and external) over the quantity of its production (profits). In my opinion it is only then that an organisation – or a society of people – describe themselves as “kaupapa driven”. This is why the imperative to ‘be kind’ is such a powerful statement of collective identity.

I cannot end any discussion about identity and relationship without reference to the beauty and physicality of Aotearoa. One of the most powerful lessons I take from my own connection to Te Ao Māori, is that the ultimate kaupapa is the taiao (natural world). I think this is why the pace layers model struck such a chord with me. Underneath all the complexity, we are all part of, and therefore dependent on, the underlying structure of the natural world.

As someone who identifies as a Pākehā New Zealander my personal connection to the whenua is not based on any sort of claim to either ownership or indigeneity. It is an expression of connection and partnership, and a willingness to learn how to belong here. It is a commitment to a shared journey of mutual understanding and growth, and the possibility of a mana enhancing relationship. Te hononga ki te mana o te whenua. Now that’s a kaupapa.

IndigiShare - Guest article with Maria Ngawati

Kaupapa as a kupu Māori or Māori word, has its origins in whakapapa. Like all Māori words and concepts, words themselves have no bearing or meaning without context. Therefore, it can be said that without whakapapa, kaupapa has no meaning – or a lack of depth.

Kia ū ki te papa

Stay steadfast, grounded, resolute

Whakapapa is the layering of genealogies, and is central to Māoridom itself. We, as Māori, are one of a myriad of Indigenous peoples that can whakapapa, or connect ourselves, to the beginnings of time and creation, and recite this connection as the layers that concrete one’s identity to a purpose, place or person – and therefore, to a kaupapa.

Just as whakapapa and kaupapa go hand in hand, they are also bereft without strong grounding in the right values. We have heard of them:

- Whanaungatanga – kinship

- Manaakitanga – respect, generosity and care for others

- Kotahitanga – unity, as some examples.

It is the tanga aspect of these kupu or ‘actioning’ of these verbs that makes them workable values.

Without a tangible actioning of values, layered in a way that enables connection – your kaupapa will lack depth, applicability, and accountability to whom it belongs.

Why is this all important? Because it provides a level of obligation towards the continued success of a kaupapa. If you are all inherently a part of something, you are less likely to want it to fail. If you can see an intergenerational benefit that extends past the individual, but manifests because of your commitment, you are more likely to give. And if you know that a kaupapa has its origins in a meaning that is bigger than self, and gives you a roadmap forward because it has happened successfully before, you will be braver as a result and less fearful of the future. This is the power and contribution that indigenous knowledge has when laying down what a kaupapa should be.

E kore au e ngaro, he kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea.

I shall never be lost, I am a seed sown from Rangiātea.

The other aspect to kaupapa, is the intangible or metaphysical connection that is manifested through whakapapa. The obligation that arises because of this, isn’t just something you should do, it’s something you are compelled to do. There are certain wairua attributed to different kaupapa. If a kaupapa is built in a strong wairua connection, then it has its own energy and energy exchange.

Priorities can be seen as being like layers, much like whakapapa. These fall out of all of those areas; kaupapa, whakapapa, values and wairua – and are imbued with aspects of obligation.

To get to this point, you have to ask yourself at the beginning of the process:

- Is there a whakapapa to this kaupapa?

- What are the inherent values of this that are connected to the whakapapa?

- How are our priorities derived from the values of this kaupapa?

- What is the intangible element or wairua of this kaupapa that may impact on those involved?

You can see then that this is very different to a conventional business strategy, or manifesto.

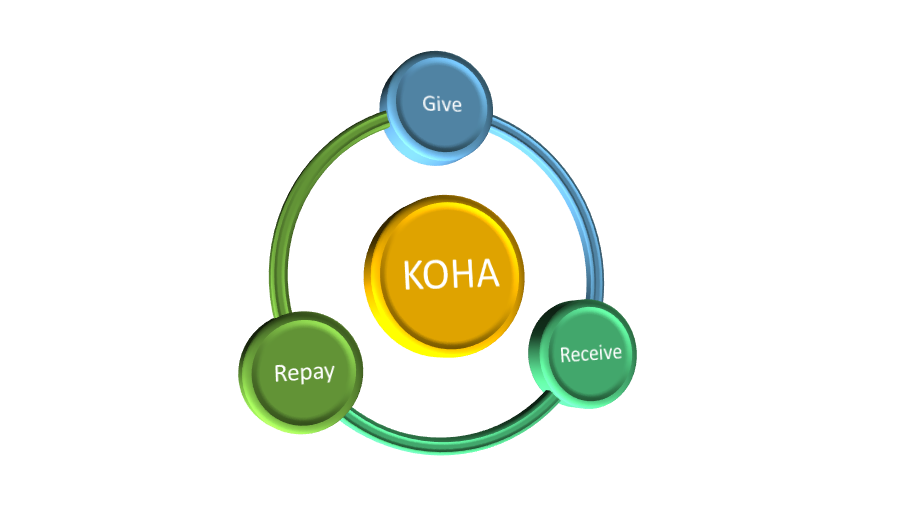

So how do you create a system that is grounded in these principles, but naturally at odds with a monetary system that, in some cases, has created profit for some people, but has largely widened the gaps in society between the “haves” and the “have nots”? By keeping the kaupapa of koha at the center. Koha is the act of giving, offering or contributing, that is built upon relationships and is governed by reciprocity.

It is the reciprocity element of Koha that we most often forget about.

It is the reciprocity aspect of Koha that is most often forgotten about (especially in the financial world), and even more so if it isn’t presented in context. There are very few contexts that display the practice of Koha better, than at tangihanga (funerals), and in how Māoridom responded to vulnerable communities when COVID-19 hit our shores.

How Māori have responded through the current pandemic crisis, is just what we know and have always known – that the most important thing in the world is people. To give weight to this, when considering the intergenerational reality of Māori small and medium business and enterprise, it is suggested that we reframe our understanding of the Māori economy and return to our traditional indigenous perspectives of social and economic activities, and to our people.

Characteristics of Indigenous economy are a philosophical space driving economic activity that is associated with the respective Indigenous worldview (which therefore informs the central cultural values, sustains customary social relationships, defines identities, and shapes personal and cultural well-being); and an approach that values “accumulation of sharing” (equitable distribution of wealth among the community). Rauna Kuokkanen

Māori see economic growth as more than benefits that enable an individual or individual organisation to accrue wealth. Economic returns means growing economic benefits which are a means to an end - in providing the cultural, social and environmental benefits that Māori seek collectively.

“In this context, any attempt to monetise benefits from Māori land or other assets needs to acknowledge that there is intrinsic economic utility in connection to the land, and that individual success is part of ensuring collective success.” Westpac, 2016.

Colonisation did not just deprive Māori of an economic base; it imposed an individualist and Western value system at odds with the collectivist and holistic values of Māori.

So in this crisis, how do we return to our inherent values and practices around reciprocity and amalgamate them with the current legal, entity, and financial structures that are at odds with the notion of collectivism – to benefit whānau Māori?

What we have been working on here at IndigiShare is a model that will enable all of these things. What we haven’t yet found, is the impact investment that requires less than a four percent return in exchange for them being part of starting the kaupapa.

Again; ask….

- Is there a whakapapa to this kaupapa?

- What are the inherent values of this that are connected to the whakapapa?

- How are our priorities derived from the values of this kaupapa?

- What is the intangible element or wairua of this kaupapa that may impact on those involved?

IndigiShare works by

- Actualising our cultural values, and using these as a foundation for how we build our monetary systems

- Shifts the focus from an entitlement or deficit mindset, to one that focuses on shared accountability for financial wellbeing

- The dominant Western/capitalist economic model, is not reflective of the socio-economic realities that Māori live in and experience.

We need a traditional system for a modern time that enables indigenous self-reliance and resilience into the future.

IndigiShare are working towards providing two models; a Preferential Shares model, and a Koha-Loan model.

The Preferential Shares model enables givers to buy shares that are put up by existing businesses through a crowdfunding process. After a certain time period, these are able to be bought back by the business at a pre-arranged sale price. This model may help businesses raise funds to carry them through the COVID-19 period to survive, or raise capital to scale or pivot their business.

Case study example: Iwi and Ahuwhenua Trusts can raise capital by allowing iwi members to buy shares in iwi-owned businesses. This allows these businesses to raise capital from those who belong to an iwi, and add to the entity's initial or ongoing investment. Iwi members then become shareholders and investors in the businesses, and therefore each other. This is how we change the rhetoric - from iwi beneficiary, to iwi investor.

The Koha-Loan model enables borrowers to crowdfund towards their business, enterprise or ‘start-up’ costs. This model enables givers to koha an amount to a business of choice as an individual, or as part of a team. The expectation is that this will be repaid over time, and return to the giver at a zero percent rate. The givers can then use those funds to re-koha to another business if they choose. This model will help businesses raise funds to carry them through the COVID-19 period and beyond in the form of a loan to survive, raise capital to scale, or help pivot their business. This model will also help start-ups and microenterprises to raise much needed seed-funding. This model can be used to support microenterprise, start-up entrepreneurs as well as small and medium businesses.

Case study example: Whānau in communities need capital to start new streams of income due to job losses in forestry and tourism. Through this model, crowdfunding can be enabled from their ‘crowd’, whānau, and community. This helps to lift the morale/wairua hihiko of the community, and keeps the borrower accountable to the repayment terms. If one whānau succeeds, everyone succeeds.

This model also enables the use of ‘teams’. Using the ‘teams’ function, iwi entities as well as individuals can contribute to businesses with owners that affiliate to those specific iwi. This allows iwi and whānau to connect with, and contribute towards iwi members’ economic success, in the form of a loan.

The reciprocal nature of the giving-receiving-repaying and re-giving cycle, is what aligns it with our tikanga of koha.

What has been apparent during this difficult time, is the strength of connection through whakapapa and our deep-seated knowing and actioning of koha. This has been shown by our incredible iwi, hapū, and whānau mobilisation, and caring of those in need.

How we lead, how we serve and how we embody reciprocity through this time, will ultimately determine how we survive into the future. Dr Ganesh Nana alluded to this at the recent Rau Tipu Rau Ora summit when he said to Māoridom, “Don't adopt the western world's way of doing things.” He stated that community saw us through the last four months, and that being connected to the community allowed Māori to look after the most vulnerable, and that because of that - we already knew what to do.

Our whakapapa to this kaupapa is built through the Māori tenet and custom of koha.

The inherent values that are connected to the whakapapa are seen in the way that we are reshaping the current western economic and financial systems into our omnipresent traditional and indigenous ways of knowing and being – not talking about them as purely words in a dictionary.

Our priorities are derived from the values of this kaupapa: Mokopuna decisions, koha economics, whānau success, whakapapa, and intergenerational legacy - are some of the ways we will gauge and act on our priorities, and measure collective success.

Wairua credits is our term for the intangible element or wairua of this kaupapa that may impact on those involved.

To give, to receive, to pay forward and back, and care for our most vulnerable, in the knowledge that they will have the opportunity to forge a semblance of sovereignty or tino rangatiratanga over their lives, is what makes a kaupapa - a worthy one indeed.

IndigiShare Charitable Trust is made up of a diverse team of community-minded people; Rawiri Bhana, John Shortland, Anahera Waru, Serena Lal, Christina Leef, and Maria Ngawati. We are also grateful for Jane Henley’s ongoing support.