Migration: The engine driving New Zealand’s population growth

Unlike previous decades, this growth is not coming from a baby boom but from a steady flow of migrants choosing to make New Zealand their home. As natural increase - the difference between births and deaths - slows and our population ages, migration is now the primary driver of demographic change, shaping our workplaces, schools, and communities.

Statistics New Zealand (Stats NZ) projections confirm that by the mid-2030s, annual natural increase – the difference between births and deaths - will dip below 20,000, and by the 2040s, deaths may outnumber births. With fertility rates well below replacement levels (currently around 1.59 births per woman), net migration is now the primary driver underpinning New Zealand’s population growth.

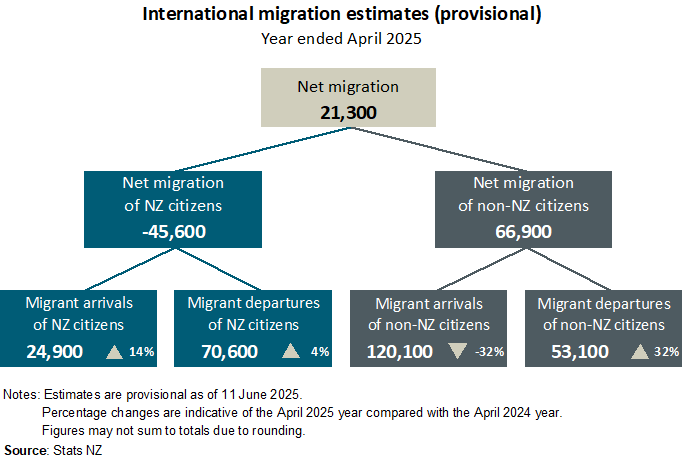

Recent data show a net gain of 21,300 migrants in the year to April 2025, with arrivals from India, China, the Philippines, and returning Kiwis leading the way. This trend is likely to continue as New Zealand remains an attractive destination for people seeking new opportunities

Why migration matters more than ever

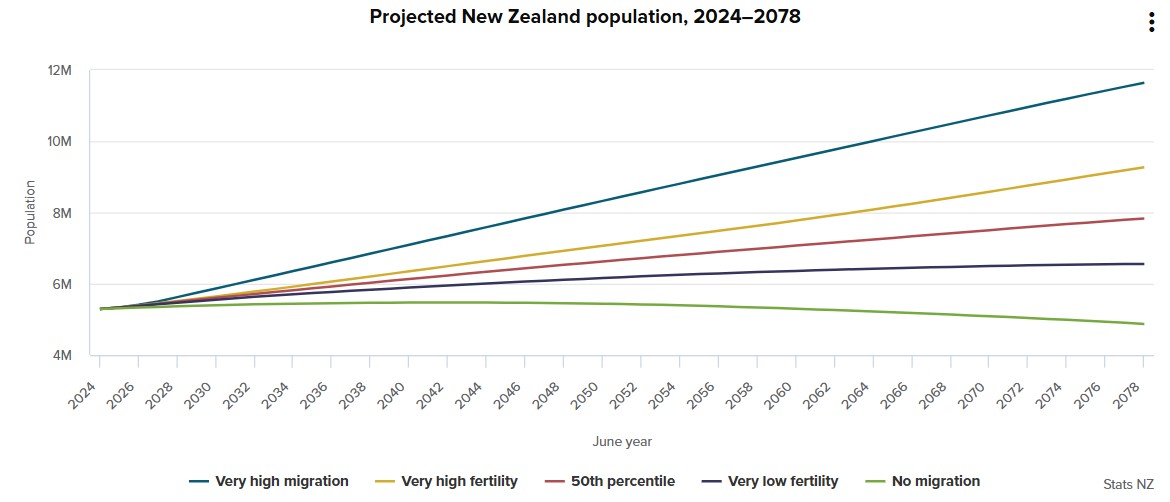

Stats NZ’s latest projections make it clear: international migration has been the main contributor to New Zealand’s population growth this century, and this is projected to continue. Two-thirds of the population growth needed to reach 6 million before 2040 is expected to come from net international migration, with the remainder from natural increase.

In a scenario with no migration, the population would peak in the early 2040s and then start to decline as deaths outnumber births. The median projection assumes a net migration gain of 42,000 people a year over the next 50 years, reflecting the ongoing importance of migration for New Zealand’s demographic future.

Employment and the labour market

Migration has played a crucial role in New Zealand’s labour market, particularly as the population ages and the workforce shrinks. Migrants, both permanent and temporary, have filled skill shortages across the economy, from highly specialised roles in IT and healthcare to lower-skilled positions in aged care and hospitality.

New Zealand relies on temporary migrants more than most other OECD countries, with a large proportion of the workforce in some industries made up of people on temporary visas. Employers in these sectors often view access to migrant labour as essential for their business. Over the past 25 years, immigration has had small but mostly positive effects on the wages and employment. of New Zealand-born workers, helping to keep unemployment low and the labour market dynamic.

Skilled permanent migrants have played an important role in filling skill gaps left by emigrating New Zealanders and bringing specialist knowledge and work experience otherwise unavailable locally. Temporary migrants, meanwhile, have become critical in industries such as dairy, where they increasingly fill entry-level roles. Immigration has reduced the risk of labour shortages for employers in diverse sectors, supporting economic resilience and productivity.

Migration also presents economic trade-offs. Productivity and productivity growth are low in New Zealand, in part because access to migrant labour has reduced the incentive to innovate and invest. Additionally, high levels of migration have placed increased demand on infrastructure and housing, affecting both new migrants and long-term residents alike. These challenges highlight the need for balanced policy approaches to maximise the benefits of migration while managing its broader impacts.

Looking ahead

As New Zealand’s population edges towards 6 million, migration will remain central to our demographic and economic future. The challenge is to ensure that the benefits of migration - economic dynamism, cultural diversity, and global connectedness - are shared widely while managing demand for education, housing, and social services.

Additionally, the benefits of a buoyant labour market have not been evenly distributed, and some industries have seen troubling patterns of exploitation, particularly among temporary migrants. Stronger protections and clearer pathways to permanent residency are needed to ensure fair treatment for all workers.

Migration is now the primary engine of population growth in Aotearoa New Zealand. How we manage this transition will shape the country’s economic and social landscape for decades to come.