Budget 2025: KiwiSaver reforms gradually shift retirement responsibility

We noted in our overall assessment of Budget 2025 our cautious optimism about the government taking a medium-term approach.

This approach includes gradually addressing the intertwined challenges of fiscal sustainability and retirement policy by making changes to KiwiSaver, namely:

- Increasing the default rate of employee and employer contributions for KiwiSaver to four percent

- Extending the government contribution and employer matching to 16- and 17-year-olds

- Halving the annual government contribution to 25 cents for each dollar a member contributes each year (up to a maximum of $260.72), making the scheme more sustainable

- Introducing means-testing, with those earning an annual income of more than $180,000 no longer receiving the government contribution.

Fiscal settings are unsustainable

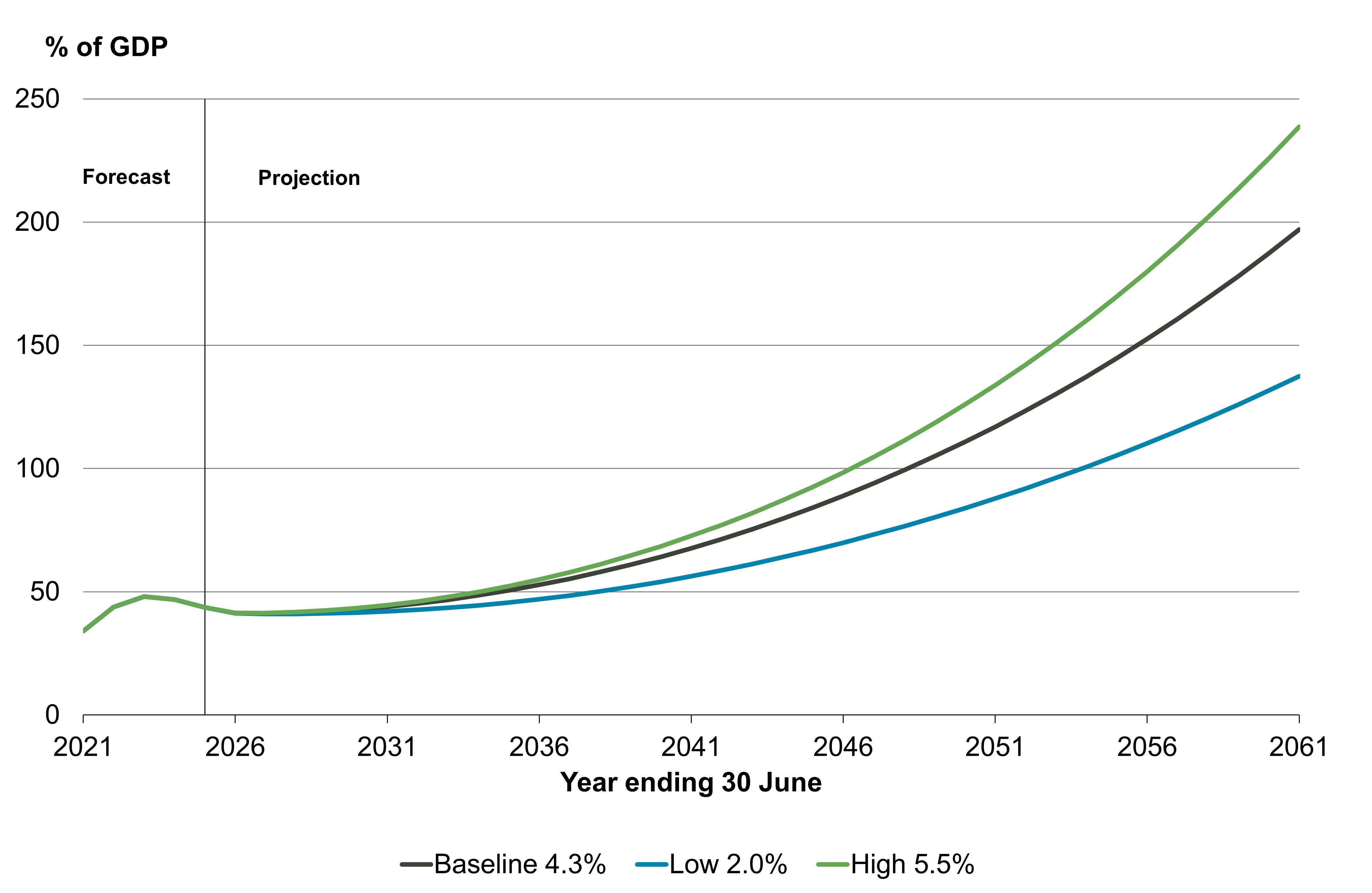

Treasury in its 2021 Long-Term Fiscal Statement concluded that:

“Our projections indicate that the gap between expenditure and revenue will grow significantly as a result of demographic change and historical trends in the absence of any offsetting action by governments. This will cause net debt to increase rapidly as a share of GDP by 2060. […] The most significant spending pressures come from a combination of healthcare and NZ Superannuation, which we project will increase by 6.4 percent of GDP from 2021 to 2061.”

Net core Crown debt as a percentage of GDP under different interest rate scenarios

Retirement policy reform, and transferring risk to the individual

The World Bank (1994) popularised the three pillars concept to classify retirement policies, defined as:

- Mandatory, publicly managed, pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) pillar to ensure the minimum level of benefits (New Zealand Superannuation (NZ Super))

- Mandatory, individually funded, privately governed save-as-you-go (SAYGO) pillar (occupational pensions or private savings), and

- Voluntary, individually funded, privately governed retirement savings scheme (KiwiSaver).

Superannuation reforms over the last 50 years, including in New Zealand, have gradually transferred the risk from the state to the individual. KiwiSaver follows this trend, with the individual bearing most of the risk.

The Retirement Commission notes that if KiwiSaver

“With its current settings, became a necessary component of retirement income, the transfer of risk from the state to the individual would be more far-reaching than in many other countries. KiwiSaver, unlike New Zealand Super, is linked to individuals’ earnings and work histories. Therefore, any changes that increase the role KiwiSaver plays in retirement income present a risk of less equitable outcomes.”

Those were the good times

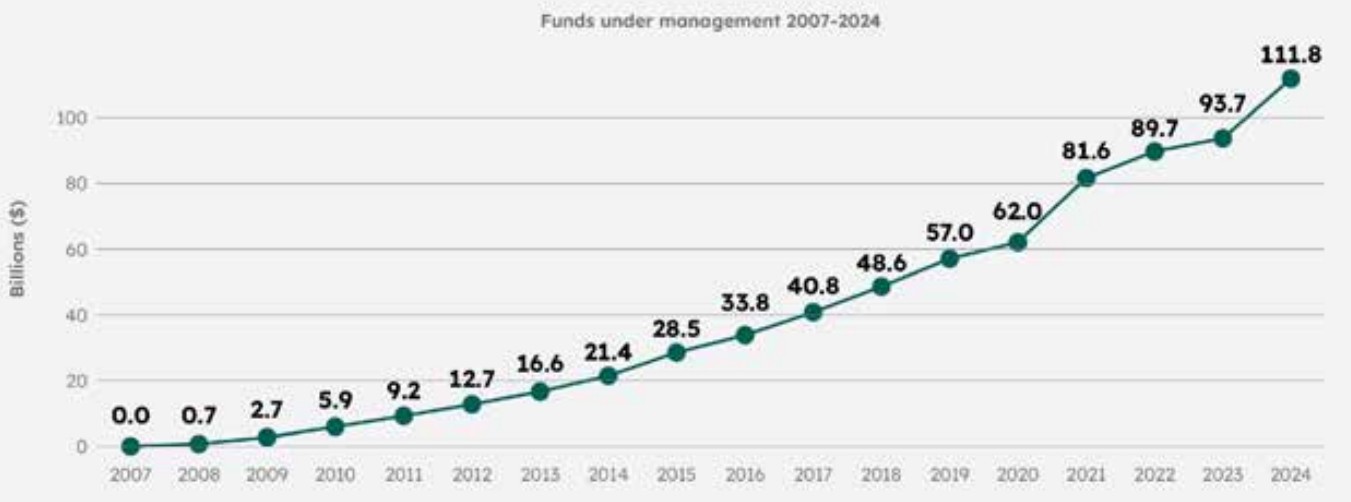

KiwiSaver balances have grown, particularly recently, with funds under management doubling in the past five years.

KiwiSaver funds under management

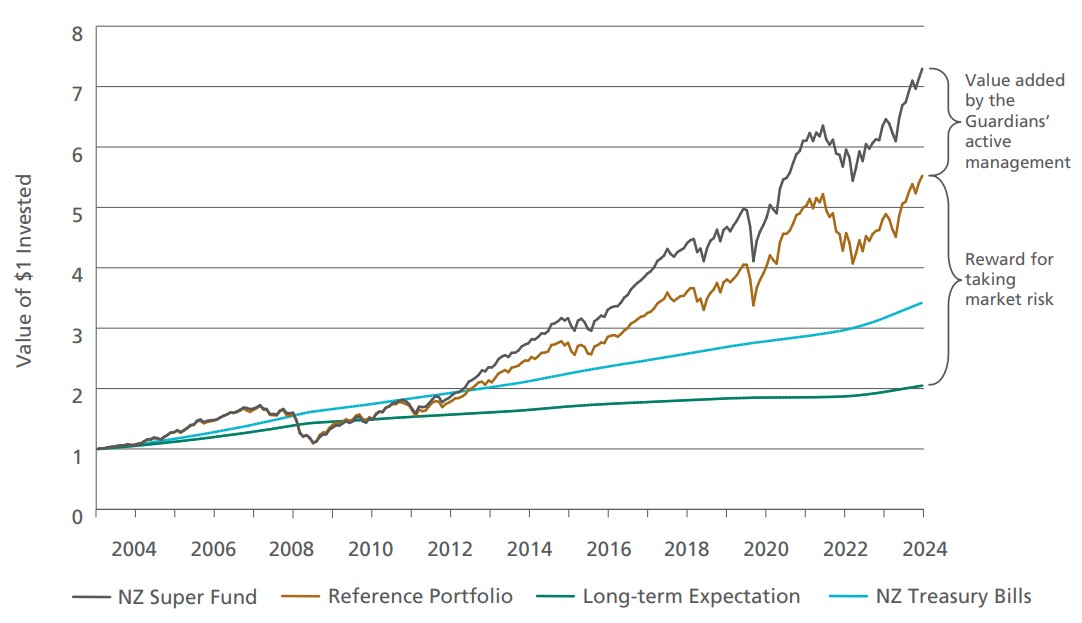

Meanwhile, the NZ Super Fund has performed relatively well.

NZ Super Fund performance

The difficulty is that the trend of transferring risk from the state to the individual to date happened under conducive market conditions, with asset prices steadily increasing.

Looking ahead: A decade of underperformance?

But this could no longer be the case, presenting not only a risk to the adequacy of retirement savings, but also a more challenging reform environment to ensure the sustainability of retirement policy models.

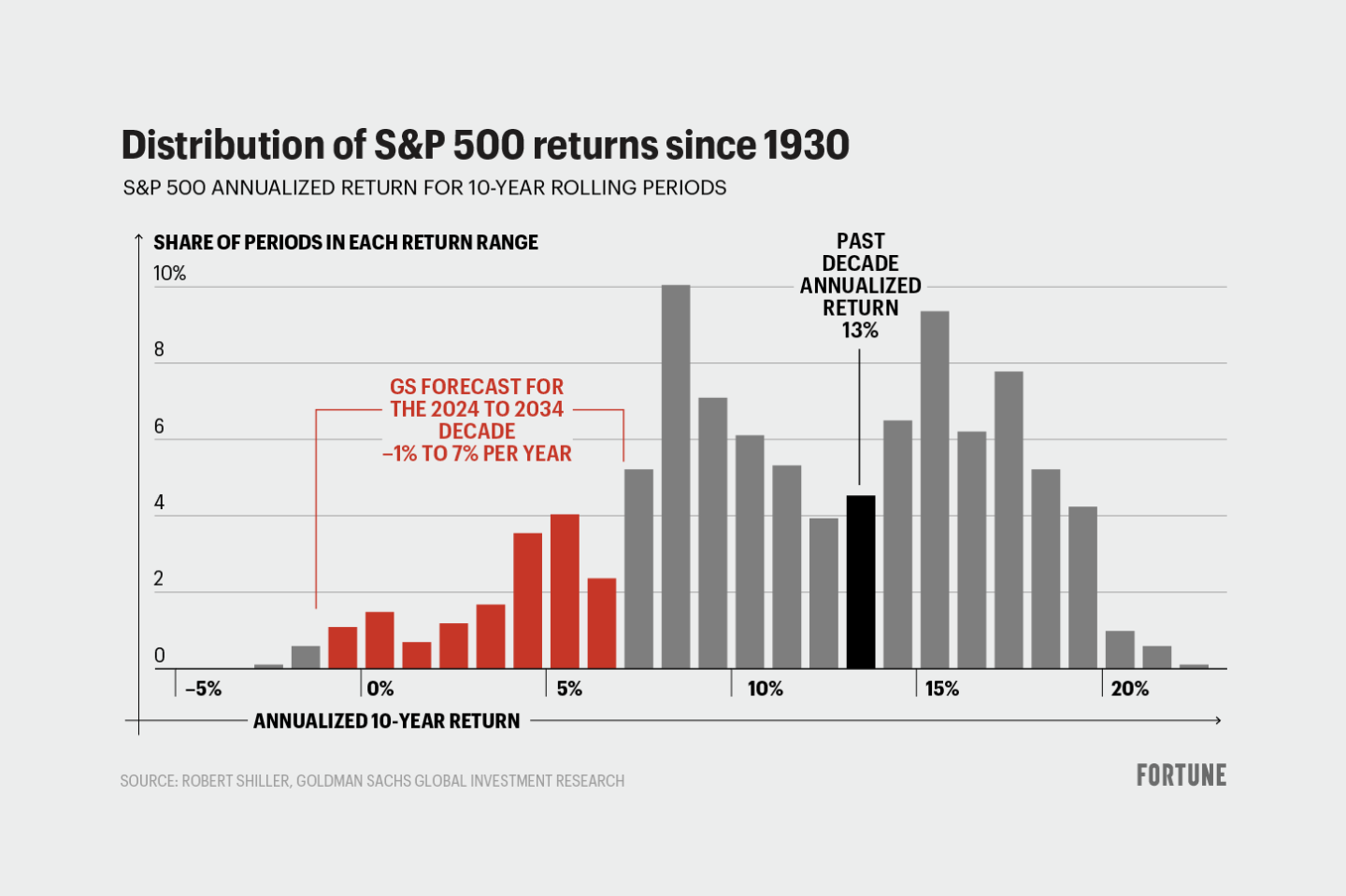

According to Goldman Sachs, the stock market performance of the past ten years could be followed by a decade of lower returns.

Distribution of S&P 500 returns since 1930

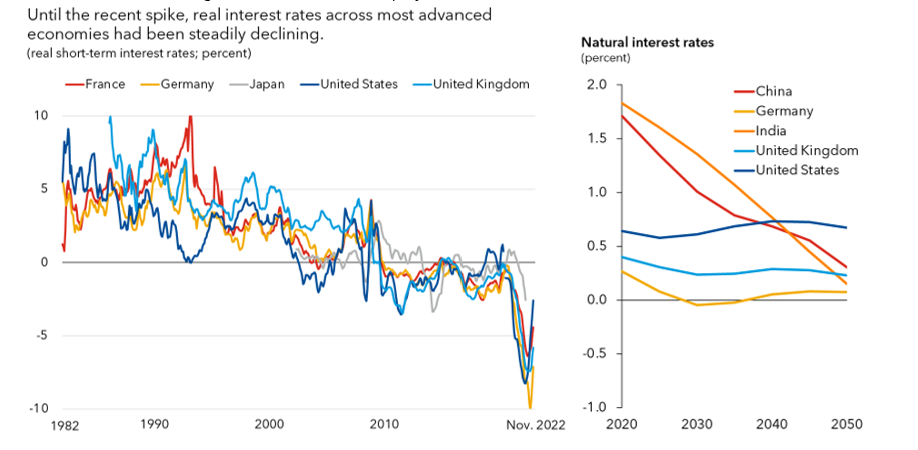

At the same time, the 40-year bond rally is over (LHS chart), with declining interest rates reaching the lower bound (bond prices are inversely related to their interest rates), while projected interest rates are not as attractive in a higher inflation environment (i.e., lower real and natural interest rates).

A four decade decline in global interest rates, and projected interest rates

A spirited debate currently engulfs the financial industry about the ongoing viability of the so-called classical investment and retirement 60/40 portfolio (60 percent stocks, 40 percent bonds), with prominent financial figures deeming it essentially “dead”.

Inherent retirement policy trade-offs

Still, the overall trend of shifting the risk of retirement savings onto individuals, combined with a possible scenario of low expected returns across asset classes in coming years, bodes for some challenging societal discussions around retirement policy reforms.

Ultimately, retirement policy design comes down to difficult political choices between the inherent trade-offs of its three core objectives – sustainability, equity, and adequacy.